Briefing: New York Leads the Way

New guidance in New York is a regulatory first for climate finance, but it will not be the last

This week, Acting Superintendent of New York’s Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) Adrienne Harris finalized guidance for New York insurers to manage climate risk, “the first time any U.S. regulator, federal or state, has publicly laid out its expectation for how financial institutions should address the risks of climate change.”

The insurance industry is a major player in the global warming money machine. Insurers are hugely exposed to the growing costs of climate disasters, and their decisions about whether to continue underwriting fossil fuel projects will help determine how costly the crisis becomes. If you’re wondering why you haven’t heard AOC or some federal policymaker talk about this, it’s probably because insurance enjoys a broad exemption from federal regulation and oversight. The power to regulate insurance companies is mostly held by state insurance regulators like Harris.

To its great credit, the NYDFS’ guidance recognizes that “the physical and transition risks resulting from climate change affect both sides of insurers’ balance sheets—assets and liabilities—as well as their business models.” Accordingly, NYDFS expects insurers to conduct “scenario analysis” to determine whether they would be solvent several decades into the future under different possible pathways for pollution and temperature increases. It is significant that NYDFS’ guidance expects insurers to strengthen their financial position in order to serve communities and consumers, instead of fleeing markets that are exposed to climate risk.

Also important is NYDFS’ affirmation that

“Technology exists today – provided by rating agencies, asset managers, and specialty service providers – to quantitatively assess the resilience of investment portfolios to transition and physical risks under a range of scenarios.”

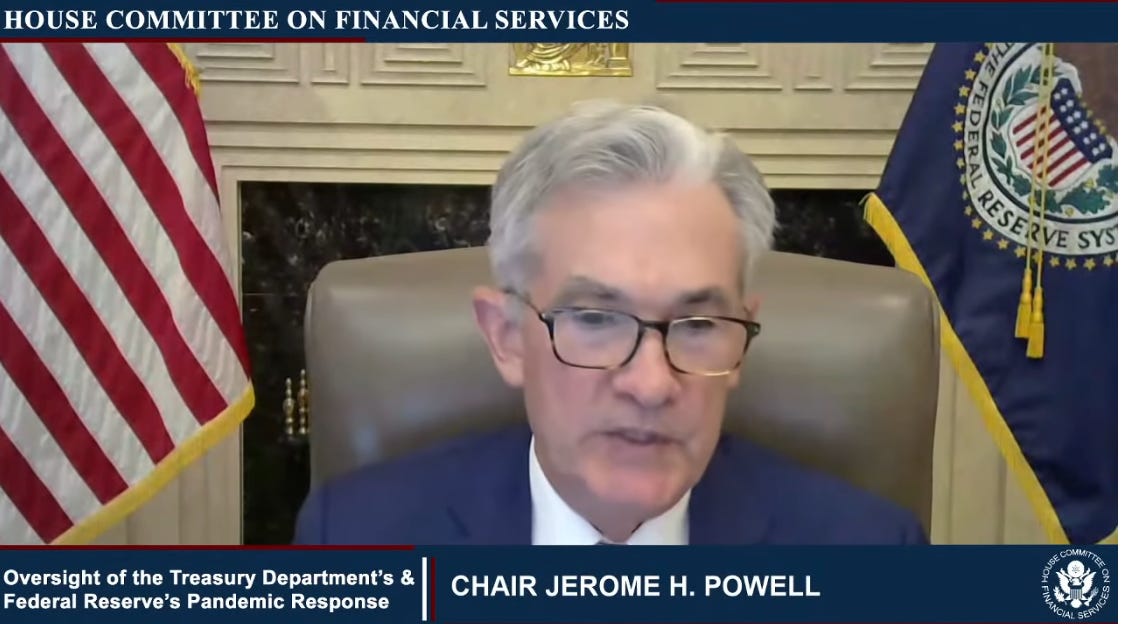

This stands in contrast to national financial regulators like Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who so far have been hiding behind the excuse that it’s “really very early days” of measuring and understanding climate risk.

To be sure, the guidance has deficiencies. For one thing, it is only guidance. And the NYDFS incorporated some but not all of the comments that were submitted by financial watchdogs and climate advocacy organizations like Public Citizen.

Still, New York has surged ahead of other state insurance regulators in seeking to reduce climate risk, and provided a template that states that are still focusing on disclosure can act on. In 2011, California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones helped lead the development of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) climate risk disclosure survey. Later, Jones built on the survey by creating a Climate Risk Carbon Initiative that required insurers to identify fossil fuel holdings in their portfolio that stood the greatest risk of becoming “stranded assets.” Today, fifteen states and Washington, D.C. require insurers above $100 million in annual premiums to respond to the NAIC’s climate risk disclosure survey. Unlike New York, they have not yet gone past disclosure requirements.

It is important to note that in taking this action, Harris merely finalized guidance that was initiated by her predecessor Linda Lacewell, who stepped down shortly after the resignation of former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. Several progressives have opposed Harris’ confirmation by the New York State Senate for a permanent role on the grounds that she is too close to the financial industry. It’s not clear yet whether aggressive climate regulation is actually a priority of Harris, who is a longtime fintech industry investor, advisor, and consultant.