The Climate Politics Almanac: Virginia's History, Part I

Our almanac first takes a look at Old Dominion, more formally known as the state of Virginia.

Over the course of Thanksgiving week, the Climate Politics Almanac, written by John Price Kepner, will review Virginia’s political history and its climate and energy politics, and conclude with an analysis of the 2021 elections. The morning news roundups will recommence next week.—Brad

1619-1865: Richmond, Capital of Virginia and the Confederacy

Virginia’s General Assembly lays claim to being the oldest legislative body in North America, having been founded to govern the Virginia colony in 1619 as the House of Burgesses in Jamestown. From 1699 to 1780, Williamsburg served as the colonial capital where the House of Burgesses met until Thomas Jefferson, acting as governor during the American Revolutionary War, pushed for Virginia’s capital to be relocated to Richmond.

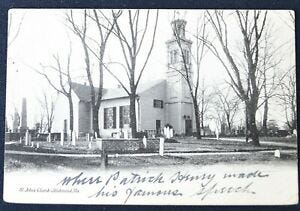

The State Capitol Building that stands today was designed by Jefferson, and its cornerstone was laid by Patrick Henry, Virginia’s 1st and 6th governor, whose famous “Give me liberty or give me death” speech was delivered from Richmond’s St. John’s Church in the run-up to the war.

Following Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860, Virginia Governor John Letcher called a convention to discuss whether the state would secede. One fiery pro-secession speech warned that:

“By the time the north shall have attained the power, the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything...Suppose they elevated Charles Sumner to the presidency? Suppose they elevated Fred Douglass, your escaped slave, to the presidency?...I say give me pestilence and famine sooner than that.”

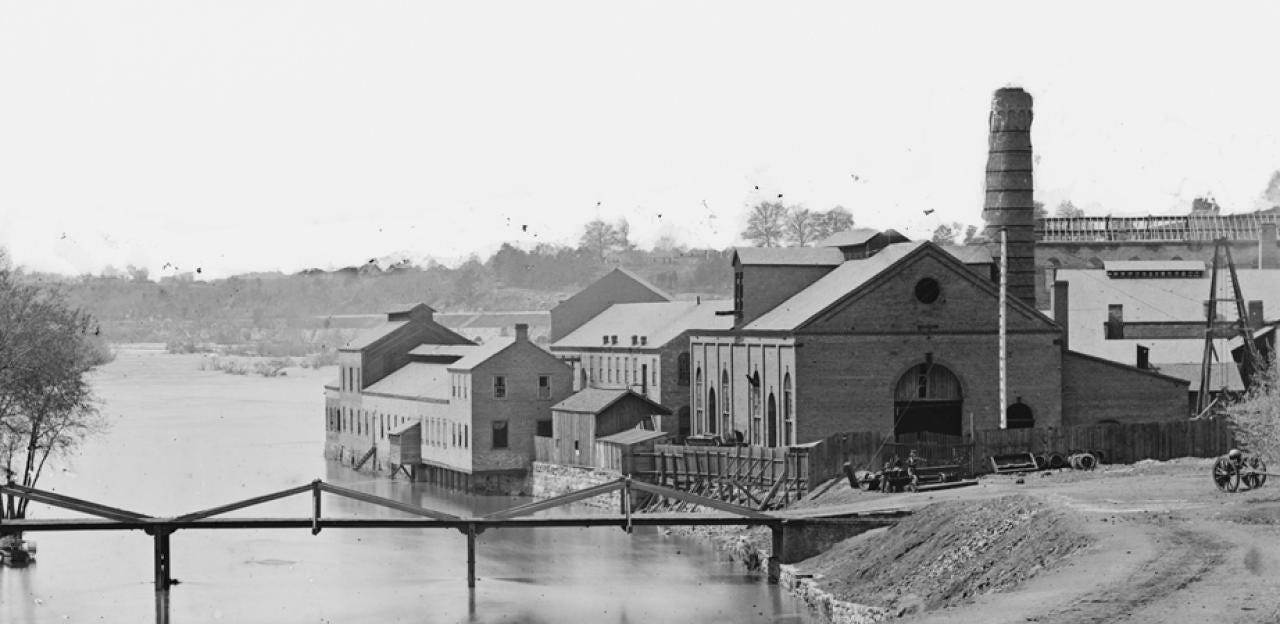

A statewide referendum was held, and white Virginians voted overwhelmingly to secede in May 1861. Shortly thereafter, the Confederate Congress selected Richmond as the capital of the Confederacy, owing to Richmond’s status as an industrial hub, especially the armory at Tredegar Iron Works, which is the modern-day site of the American Civil War Museum.

Therefore, for most of the period between 1861-1865, the Confederate Congress convened in the Virginia State Capitol.

Several blocks north of the Capitol in Richmond’s Court End neighborhood stands the so-called “White House of the Confederacy,” where Jefferson Davis and his family lived during the Civil War. For many years, the home was the site of the “Confederate Museum,” which attracted many supporters of the “lost cause.” In 2014, the house was purchased by the American Civil War Museum, and today it features historically accurate information. Walking along Richmond’s James River waterfront toward the Hollywood Cemetery (where Jefferson Davis and American presidents John Tyler and James Monroe are buried), visitors can cross a bridge that commemorates the events of April 1865, when Richmond fell and the Confederacy surrendered.

1865-1902: Reconstruction and Backlash

After the Civil War, Richmond was occupied by federal forces for five years, until 1870, when Virginia was readmitted into the Union after ratifying the “Underwood Constitution,” named for the abolitionist judge from New York who presided over the proceedings, which were boycotted by most white Virginians because they granted the right to vote to Black citizens.

During the Reconstruction era, Black Virginians began to build political power in Virginia, and the biracial Readjuster Party championed expansion of education and investment in the state infrastructure that had been destroyed by the carnage of the Civil War. Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood became known as “Black Wall Street,” organized by civic leaders such as Maggie Walker, the first Black woman to serve as a bank president.

Grievances with the corruption of state political boss Sen. Thomas Martin led to the adoption of a referendum in 1900 to hold a new constitutional convention in 1901. One hundred delegates were elected to the constitutional convention. Among the most prominent was Lynchburg News editor Carter Glass, who described the convention’s purpose as “the elimination of every Negro who can be gotten rid of, legally, without materially impairing the strength of the white electorate.”

In 1902, the convention completed its work, ratifying a new state constitution that established a poll tax and other barriers to Black voting. Glass would go on to become a major figure in state and national politics, co-founding the Federal Reserve System as Chair of the House Banking Committee in 1913, serving as Woodrow Wilson’s Treasury Secretary in the aftermath of World War I, and securing passage for the the Banking Act of 1933 (better known as Glass-Steagall) during his 26-year tenure in the US Senate.

1902-1963: Jim Crow and the Byrd Organization

The 1902 constitution enshrined Jim Crow principles into the state’s laws, and the first half of the 20th century was dominated by white supremacist machine politics in Virginia.

In her book “Democracy in Chains,” author Nancy MacLean describes the enduring influence of the late University of Virginia economist James Buchanan, who won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Economic Science [sic] for developing “public choice” theory. “Public choice” theorists stipulate that more democratic and inclusive systems of governance inevitably lead to unsustainable levels of social spending, and their work has strongly influenced right-wing institutions like the Charles Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity (headquartered in Arlington), the American Legislative Exchange Council (or ALEC, also based out of Arlington), and the Mercatus Center at Fairfax’s George Mason University.

In the 1950s, Buchanan was introduced to Senator Harry Byrd. Fueled by the backlash to the Brown v. Board decision in 1954 and other pro-civil right rulings by the Warren Court, Buchanan formed the economic philosophy behind Virginia’s legendary “Byrd machine,” which dedicated itself to a concept that is still known to this day as “the Virginia way.”

Of Byrd, MacLean writes:

“No single man has ever dominated a state so completely for so many years, albeit with studied courtliness. He presided as governor for most of the 1920s and as U.S. senator from 1933 until his retirement in 1965, acquiring a power that would have awed [John C.] Calhoun. But Harry Byrd’s Organization bore no resemblance to the machines of northern cities, with their abundant services to attract the loyalties of motley low-income electorates. It was their veritable opposite: ‘the united establishment of Virginia,’ one authority on Virginia politics has observed, over which ‘Byrd functioned as chairman.’ Its aim was to insulate government from citizen pressure on public spending or other reform...One liberal scold called the senator ‘a steadfast opponent of most of the twentieth century...as chair of the all-powerful Senate Finance Committee, Byrd ‘measured his success as a senator not by what he passed, but what he stopped from passing.’”

The Byrd Organization relied heavily on Jim Crow tactics bolstered by the 1902 constitution, including the poll tax and the practice of drawing districts that magnified the power of legislators representing less populous areas. Consequently, MacLean notes, “the Byrd organization had to win only about 10 percent of the potential electorate to hold on to power.”

While the “Virginia Way” is usually used to denote moderate statesmanship, Byrd and Buchanan’s public choice adherents molded it into a philosophy that the state should be governed by a strong partnership between business and politics, with the law dictated by an elite coalition of segregationist politicians and wealthy inheritors of the state’s old planter class.

In 1947, Governor William Tuck, a notorious union-buster and major ally of Byrd, signed one of the nation’s first right-to-work laws into effect, as Virginia signaled a precursor to the Taft-Hartley Act that Congress approved later that year. In national politics, Byrd is best known for organizing the 1956 “Southern Manifesto,” through which over 100 Members of Congress pledged “massive resistance” to school integration, including the passage of state laws like Virginia’s restraining local control and denying public funds to integrated schools.

1966-1999: Genteel Conservatism

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act in 1964 and 1965 coincided with Byrd’s retirement and death in 1966, and as the Byrd Organization began to subside, Virginia joined most southern states in drifting toward the Republican Party. During this period, “Howlin’ Henry” Howell emerged as one of the only successful examples of progressive populism in Virginia’s political history. Howell supported school integration, fought to repeal right-to-work, successfully waged a legal battle against overrepresentation of rural communities in redistricting, and railed against the Byrd Machine and monopolies, especially Dominion Energy (known as VEPCO at the time), which he called the “Very Expensive Power Company.”

Howell’s tepid endorsement of the Democratic candidate for governor in 1969 was seen as a factor in enabling Linwood Hilton to be elected Virginia’s first Republican governor in the 20th century. Howell was elected Lieutenant Governor in 1971, but he failed in three attempts to win the governorship, coming closest in 1973, when he lost to Mills Godwin, a Byrd loyalist and former Democratic governor who switched parties and won election as a Republican.

In 1971, Virginia ratified a new constitution that replaced the Jim Crow era constitution, eradicating the 1902 constitution’s poll tax and forced public school segregation, and enshrining a “one person, one vote” principle.

That same year, the Supreme Court’s decision in Perkins v. Matthews required Richmond to submit for court approval a plan to annex 23 miles of Richmond land to Chesterfield County, thus reducing Richmond’s Black population from 52% to 42% of city residents. Ultimately, the Court approved the annexation plan, but required city councilmembers in Richmond to be elected in district elections rather than at-large. Five of Richmond’s nine council districts were drawn with majority Black populations, and for several decades, Richmond used a council-manager form of government where the mayor was selected by the city council.

Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Virginia continued to serve as a safe haven for genteel conservatism, with the GOP electing numerous statewide officials, such as John Warner (senator from 1979-2009, famous for his brief marriage to Elizabeth Taylor and championing of bloated military budgets) and George Allen (governor from 1994-1998/senator from 2001-2007, and famous for his “macaca” comment and general racism); while Democrats elected centrists such as Chuck Robb (governor from 1982-1986/senator from 1989-2001, famous for his marriage to LBJ’s daughter and victory over Oliver North in a bizarre and notorious 1994 campaign).

Despite Virginia’s Republican tilt at the presidential and gubernatorial level in the 1970s and 1980s, it wasn’t until 1999 that Republican majorities in the General Assembly were elected, giving Virginia its first Republican trifecta midway through Governor Jim Gilmore’s term. This was the high-water mark of Republican governance in Virginia.

Our next post will bring us up to present-day Virginia.